Suzanne Ciani: Exploring in the moment is alive

My interview with synthesizer music pioneer Suzanne Ciani

My family is in Iceland, attending (or, you know, playing) Wilco’s residency in Reykjavik. We’ve spent the past few days luckily traveling around, seeing some of the thousands of waterfalls and moss-covered volcanic barrens that make the country feel like a magical elven land to tourists and, apparently, also to locals.

I’ll post more from the trip but today I want to share this adapted excerpt from Mirror Sound in honor / anticipation of my book collaborator (and Grammy-winning designer, hehe) Lawrence Azerrad’s public event with Suzanne at the California College of the Arts taking place in San Francisco this Friday, April 7.

From 2017-2019, Lawrence and I co-created a book about musicians who engineer and produce their own music, Mirror Sound. The book came out in 2020, right in the meat of lockdown time, which made the themes of the book—making records wherever you can, with whatever is available to you—seem more relevant, even though we were upset about why they became more relevant.

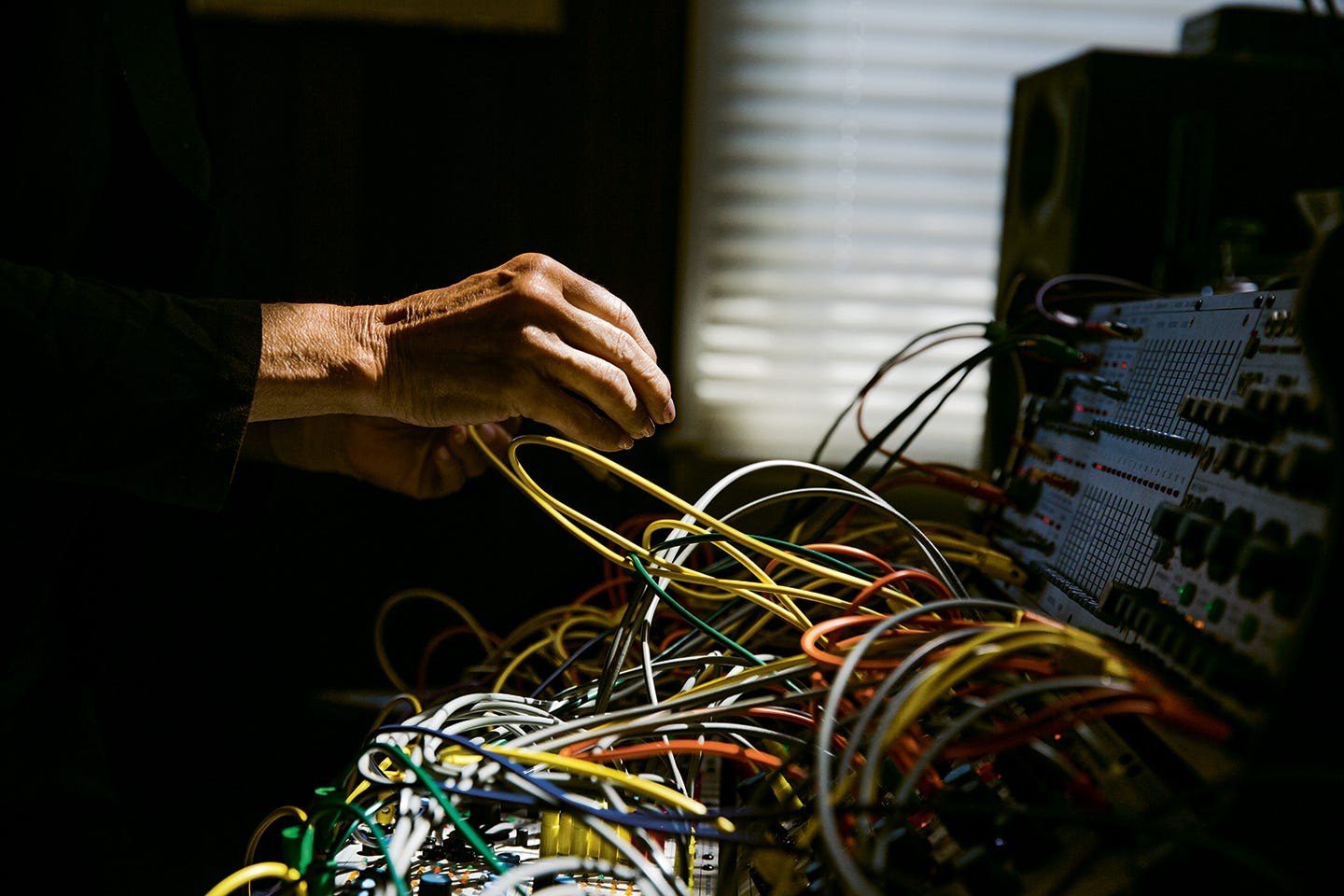

In the course of making the book I interviewed Suzanne Ciani, the pioneering musician who helped popularize synthesized sound in pop, classical music, and sound design. For a time she even assembled synthesizers in the workshop of legendary electronics designer Don Buchla, the inventor behind beloved, predictably unpredictable instruments like the Music Easel. Suzanne says Don’s tools, which she still uses, are practically living creatures. “I look at the Buchla now and it’s not the same Buchla I had last year… It sat there for a year before it came alive.”

In 1974 Suzanne moved from California to New York City, where she cold-called advertising agencies until they let her in on commercial sound design projects. Within a few years, she was an in-demand session musician and had created some of the most-heard sounds on Earth, like Coca-Cola’s signature “pop, pour, fizz.”

Despite her success in session work, record labels in New York weren’t willing to give Suzanne a deal to work on her original solo music. She’d ask for a contract and they’d offer to set her up in a studio with traditional instrumentalists as if she were a female vocalist fitting into the cookie-cutter of solo pop material. They didn’t get what she was trying to do. Luckily, around that same time, Lily Tomlin hired Suzanne to soundtrack a movie, The Incredible Shrinking Woman, and it gave her a windfall with which to build a fully equipped recording studio inside her apartment in Manhattan, a rarity at the time.

“I took that wad of cash and I redesigned my living room, put something down over the carpet, moved in a console, got a Synclavier,” Suzanne told me. “I hadn’t realized how exotic it was at the time. Everything just seemed so naturally evolving to me.”

(At one point after building her studio, Dolly Parton visited, saw the freedom it afforded Suzanne, and told her manager, “We got to get me one of these!”)

Suzanne moved the studio from her living room to an entire floor of a separate space on Twenty-Third Street in Manhattan in 1986. That new studio was kind of too big to feel comfortable. “I didn’t like having a studio where I needed [another engineer] just to power it up. It was so big ... I’m always happiest in my intimate space in my home and my home has always had a kitchen next door.” So after a health-related trip back west in 1993, she packed up her Buchla, sold most of the rest, and moved to California, where we visited her.

When Daniel Topete, the book’s amazing photographer, and I showed up at her house, she immediately showered us with Italian hospitality, offering us strawberries, sparkling water and chocolate. We stepped right into her studio: a living room with a grand piano, a synthesizer station, a rack of recording equipment, and a picture window to the Pacific ocean.

“Now I do everything myself here in this remoter place and I’m happy to kind of just do it all. I sit here and I’m just happy as can be,” she told me. Suzanne sits on a bench in between her synthesizers and her piano, a physical illustration of her dual identity as a classical composer and a technological explorer. And she creates all the time. The select instruments on her desk are always turned on, changing, revealing themselves to her.

Interview with Suzanne Ciani

California, 2019, edited and abridged.

Spencer Tweedy: Did recording play into the composition process for Seven Waves (1982) at all or did that not come in until later when you had your own environment?

Suzanne Ciani: Oh, totally. Yeah, I mean, because it was electronic. It didn’t exist until it was recorded.

I started out on the Buchla [synthesizer]. And so I was doing pure analog for ten years. Then I landed in New York to do a Buchla concert and I needed to make a living. And I made a living with the Buchla, designing sounds. But by that time, there was, you know—the revolution occurred. The Japanese got involved. There was Yamaha, there was Roland, this influx of large corporate people, and I became a clearinghouse for all that new stuff because I was the tech person in New York. So they all gave me tons and truckloads of stuff and I would design sounds for the DX7 and then I would use those sounds in my Seven Waves.

ST: Wow—so when you buy a DX7, some of the presets are sounds you designed?

SC: Yeah, some of them are my sounds. I love those sounds. You could do amazing stuff.

ST: I know you have a special relationship with the Buchla, but when you were moving into the world of other instruments did you find that some were really conducive to your creating and some were an impediment?

SC: Because of the Buchla, I was basically oriented toward non-keyboard interaction. So, even if I used a then-current, new machine that always came out with a keyboard, I would tend to be programming it, and using the keys to trigger whatever I had designed. I was trained as a pianist, so I had one producer say to me, “For heaven’s sake, you can read anything, you can play anything, would you please just get an ARP String Ensemble [string emulation synthesizer] and come and do our string parts?” And I said, “Well, I don’t believe in that. That’s not the proper use of electronic language.” And he said, “For God’s sake, I’ll buy you the instrument and you play it.” And so that’s how I started doing that type of session work … I remember once I was hired to do a disco bass and they had the volume—it was in Philadelphia, I think—the volume was so loud that at the end I had actually injured my hand on the [Buchla] touch plate [keyboard]. Because, you know, it’s not resilient. It’s not meant to be banged. But if you’re banging a disco beat, you can break something.

ST: As you moved from live performance to recording, what was your workflow like? How did you keep track of ideas and accumulate material?

SC: At that point I had been bruised and battered by the real world to some degree. I got the message that nobody was ready for my pure Buchla. The electronic stuff, the pure electronic stuff, non-keyboard, wasn’t understood, for one thing. I mean, even if I played, people didn’t know where the sound was coming from. Even today, I have to say, some of them don’t know where the sound’s coming from. They think there are samples in there. It’s, like, oh my God. So, I couldn’t do the pure Buchla.

I have a classical background. I am a composer. I have a master’s degree in music composition from the University of California, Berkeley. And my solution to my first recorded project was to do it completely electronically, but to use melody—my Italian heritage, my classical romantic heritage, and something that I loved. And I combined my classical world with the magical things that I loved about technology: the fact that I could play very slowly; the fact that I could create a safe space because the machine was so dependable and you could feel this womb of safety with the machine—the sensuality of the machine. I always thought of the machines as sensual … So that was the synthesis of the classical world with the world of technology. And it was recorded. And it was a combination of very specified notes in composition and open spaces for improvisation, you know, doing the things that you can't really notate.

“I combined my classical world with the magical things that I loved about technology: the fact that I could play very slowly; the fact that I could create a safe space because the machine was so dependable.”

ST: Did you ever feel that there was a tension between the “dependability” of your instruments and ensuring that they don’t become too predictable? Because dependability means that there’s a certain level of repetition.

SC: I know what you’re saying. And the Buchla—you know, as I say, [Don Buchla] was the Leonardo da Vinci of musical instruments. And I was really indoctrinated by his concepts. And that machine is a living thing. And so there was no stasis. It was always in flux. And that was the nature of it—to be in movement. And I always say that it wasn’t about the sound, but about the way the sound could move.

ST: Yeah. Not about timbres.

SC: Everything was alive and changing. It was not sampled. I think in digital technology we have experienced a lot of, you know, cutting and pasting and literal repetition and getting stuck someplace. But that was not the world that I came from with the Buchla.

ST: Did you view the technical processes of recording as being yet another facet of the expression, or did you view them as secondary and separate from your creation of music?

SC: When you’re working in electronic music—and today I think this is the case overall—you’re in the control room, and the traditional functions of the control room become part of your palette. You have hands-on for the reverb, you have hands-on for the EQ. So you’re kind of an engineer, and, you know, it’s all one thing. This is not to say that it wasn’t a complete teamwork thing. It was. I had Mitch Farber, who actually laid out the scores on paper. Leslie Mona … the first pieces were mixed by different people.

ST: What does your typical music-making day look like now with this new setup?

SC: Well, you know, it’s so funny because when I got rid of my big studio, I said I’m never going to do that again. I didn’t like having a studio where I needed somebody just to power it up; it was so big … So I have certain rules. I only have what I’m actually using in the studio at any particular time. And that changes …

There’s this whole discussion now about the way technology impacts composition. And this is a real dynamic. And it’s fascinating. It’s unavoidable. I mean, I love Handel, I love Mozart, Beethoven, whatever. But let’s be honest! We’re living in a world now where the building blocks of composition have changed. And that’s not to say—you talked about repetition and all of that—I still want to keep things fluid … I’m one of the only composers I know who doesn’t use Ableton [audio workstation software].

ST: Or [Avid] Sibelius [composition software]?

SC: Or Sibelius. For me, it just doesn’t fit. I mean, it might. Maybe I’m being too close-minded.

ST: That’d be hard to say. Someone who’s still experimenting with so much equipment and so many processes—close-minded wouldn’t be fair.

SC: No, not close-minded. The thing is, I like the Ableton developers and I’ve been teaching at Berklee College of Music a couple of times a year, and I noticed that all the kids are madly into Ableton. So I know how it’s taken over the world. And I think they’ve done a wonderful thing for a lot of young musicians. But it’s not my thing. And I think that’s the value of who I am in this day—that I come from a different value system, the early days of analog, when there was something that sparked a different approach back then and we are revisiting what that was all about. Analog is alive now, exploring in the moment is alive now. Non-sampling is alive now. Interactive in the moment is alive now. And that’s where I came from a long time ago.

Thank you to Suzanne for allowing us into her space and speaking with me. Thanks, of course, to everyone who helped Lawrence, Daniel and me make our book (Holly! John!). For more information about Mirror Sound, see the book’s website or Bookshop.org.

Spencer

I love substack but this is easily my favourite piece on here so far, thank you so much! I'm absolutely having that book

Thank you (and Suzanne) for firing up my imagination this morning! And since you mentioned chocolate, my favorite Icelandic chocolate is Hraun! Please find some and try it out. Hraun is the Icelandic word for lava. Imagine something like a nestle crunch but made by a not-evil company that actually wants to make excellent chocolate. I was in Iceland in 2010 when my daughter was studying abroad there and we still order Hraun and hot dogs once in awhile from an Icelandic food importer. I hope to go back some day.