Eat a Peachfork

I look forward to the world wide websites yet to come, the apps that freaks will build

There’s a lot of concern for the future of music journalism since Condé Nast merge-killed Pitchfork.com into Gentleman’s Quarterly last month. (At least that’s what they seem to have done; it’s all a little murky right now.)

I’m worried too about the decline of opportunities for critics to support themselves, for listeners to find inspired curation rather than algorithmic suggestion, and for artists to build an audience.

I’m not worried about the perpetual existence of small scenes, groups of friends who are mercifully detached from macro-trends of media consolidation, who make stuff with the tools available to them, and who have an impact despite the humbleness of their materials, their reach, and their access.

But more on that in a sec, I want to cast soft aspersions on corporate directors first.

Nobody seems to know yet exactly why Condé Nast won’t let Pitchfork continue as a standalone publication. We could assume it’s about declining readership and therefore ad dollars, but Pitchfork is still one of the most-visited websites in Condé Nast’s portfolio.

It has something to do with money, and if it has something to do with money, I suspect it has to do with the industry’s broader challenge of attracting advertisers while herds of readers move on to graze in greener, tech-ier fields.

Granted, I’ve never run a 115-year-old media conglomerate. But I can’t help but feel like that challenge would be surmountable if directors were more dedicated to improving customer experiences, investing in new modes of distribution (way beyond “a social media strategy”), and sacrificing excesses of high-rolling old times. (Unless the only way to get that A-list interview is really to have Class A office space.)

Twelve years ago even legacy media companies like The New York Times were experimenting with multimedia storytelling that won them a Pulitzer. Flipboard was making an iPad app that resembled the moving-picture fantasy newspapers of Harry Potter. Pitchfork itself was a fast, easy-to-read website and their Pitchfork.tv columns, like Juan’s Basement, were some of the funnest ways to find out about music on the internet.

The torch of internet experimentation is obviously, beautifully still carried by people all over the world. (So too is the torch of music journalism.) But I don’t see it carried by legacy companies the way it could be if their directors’ response to social media were different. We could and should still be seeing wild innovation from Wired.com and Pitchfork.com. Their presences on the web, the main way readers interact with them, should be as forward-thinking as the scientists and artists they cover, respectively.

Instead, titans of the industry seem to think the best way to entice advertisers is to run ads that are bigger and more obtrusive than ever, and that the best place to cut costs is from the bottom of the org chart. There’s a lot I don’t know about their business, but I can’t help but judge them for that.

In the meantime, thankfully, there are publications that show another path. In 2017, DNAInfo was the most useful local news outlet in Chicago and New York. After its staff tried to unionize and its billionaire owner shut the whole thing down, its former editors restarted it as a nonprofit, Block Club Chicago. Same appearance, same culture, same quality. And it’s been going strong, supported by readers and grants, for seven years. It was painful then, but the publication and the city are in a fairer, stabler situation now because it transitioned from a top-down company into a reader- and patronage-supported one.

As a subsidiary of Condé Nast, Pitchfork didn’t make enough money to pay its share of rent in One World Trade Center. It seems.

As an independent, ad-supported media company like it once was, or, we could imagine, as a low-overhead membership business, Pitchfork has a revenue bar it can meet. Pay for servers and pay for contributors to live and eat. Invent interesting ways (again) to spread the word about music. There are enough “passionate millennial males” (and more) with wallets for that.

That’s the thing: it’s 2024, and you can still start and run a website for not very many dollars. Or photocopy a zine. Writers need to be paid, yes; the core technology, the core resources a publication needs to do that—they’re relatively cheap.

So if our favored music publication can’t meet the distastefully high revenue bar set by a board chaired by a billionaire, so be it.

Let’s make some zines and websites again.

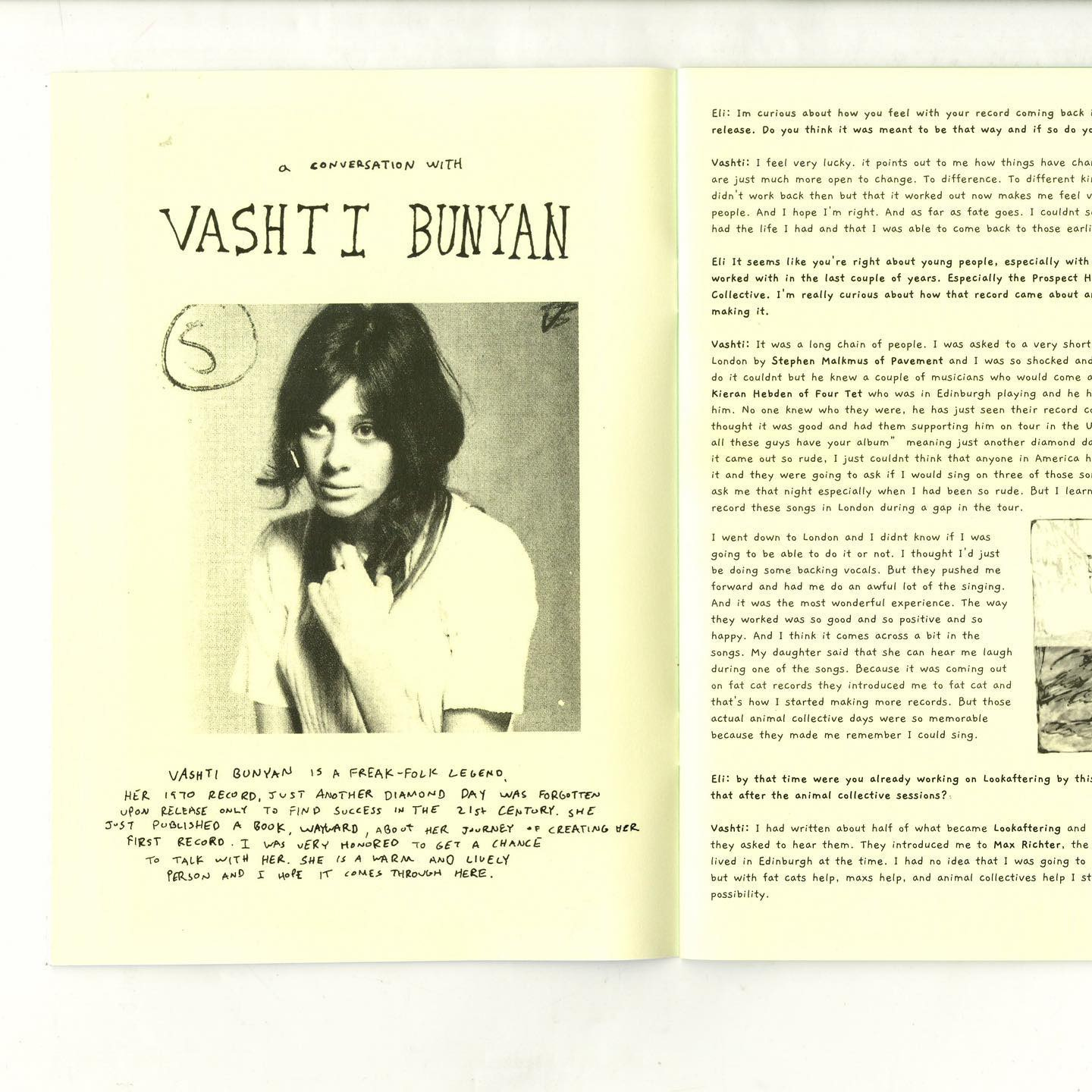

Like: Unresolved. By my friend Eli Schmitt.

Eli makes Unresolved with the time-honored Ways of the Zine: typewriters, scissors, photocopies, staples. To my eyes, Unresolved is anachronistic but not contrived. Paper is the medium Eli actually wants to use; pen drawings and stark cutouts and splotchy typesetting are the appearance that feels good to him, and it feels good to me.

Maybe most importantly, he has careful taste, so he finds interesting artists, and then he interviews them. The agenda is set by Eli’s listening. Cool!!! It’s fun to listen to stuff that a writer actually wants to listen to. (Don’t get me wrong, we need press releases and journalists who are willing to run with them. But it’s lovely when writers get to sing about the music they like.)

Eli’s reporting on art and live show curation are so sincere and useful that NPR and The Chicago Reader have covered them.

I still want a healthier mass media. I want websites you can read without turning your device’s processor into a huffing furnace, and mind-expanding apps again. There’s a sweet spot of scale for music media we’re clearly not living in right now. It’s hard to tour, hard to sell records without busy public squares in which to introduce (and reintroduce) yourself to people.1 And with each public square that dies, the illusion that attention for one’s art is a scarce resource, and therefore that the art market is a competitive zero-sum game, becomes harder to shoo away.

We don’t want a return to the monoculture of the sixties—ABC, CBS, NBC—nor to the days of radio payola, nor to… the times before all of that. We do want music and art publications that actually report on releases and shows and attitudes and places you might not know about—artists with and without institutional support—and publications that interpret others’ work in beautiful (or harsh or funny) ways. You know, like Pitchfork did, even at its snarkiest and like it does even now in its zombie state.

In the meantime—and always—we have Unresolved.

Three more places to find out about new music

Plus, the new old reliable, Stereogum. And SPIN, Uncut, Under the Radar, Consequence, et al.

There’s a whole other can of worms in the struggle and survival of fairly run, well-loved and well-attended music venues.

Ooooh how I could forget these too:

http://radio.garden/

https://www.nts.live/

https://daily.bandcamp.com/features/welcome-to-bandcamp-daily

https://chirpradio.org/

https://radiooooo.com/

YOUR LOCAL COLLEGE/COMMUNITY RADIO!

Yes! To all of this! I was fortunate enough to spend a few years in the career I dreamed of as a kid—music journalism and criticism. And unfortunate enough to have my career align with the shift from paper to internet. I started at an “alt” weekly, although “alt” is in quotes because the paper was owned by the Village Voice corporation. That should have been a point of pride, but being a part of their ham-fisted attempts to be relevant in the digital world was humiliating. I had a great time writing for a financially independent magazine for a few years, where I had the freedom to explore my own tastes. In the end they couldn’t keep up financially and folded. Even writing for the not-for-profit community radio station near me ended when the board and director decided to use the corporate business model for running their non-profit.

And that’s why I have a day job in copywriting and save my music writing for Substack. It’s disappointing, but I love to see how music journalism keeps reinventing itself when corporations keep trying to kill it.