I’m home from a land where custodians’ electronic carts sing songs.

Where bottled tea is warm and fish is fresh in every corner store.

Where Wilco and Finom played to sweet, attentive crowds last week.

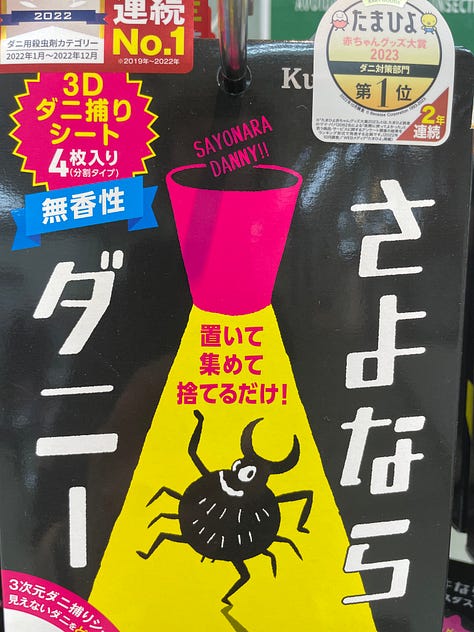

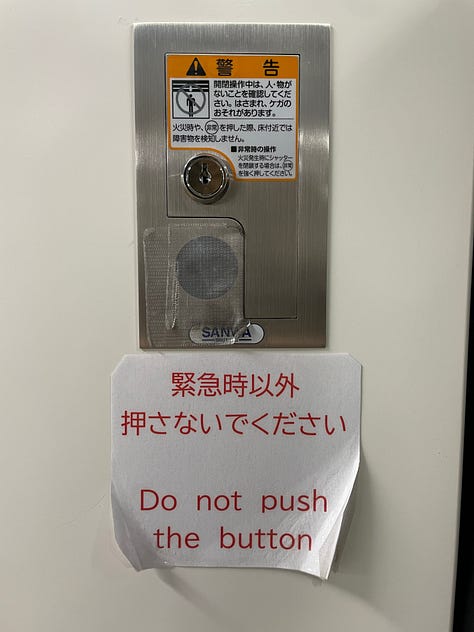

There’s so much to love about Japan. It looms large in America for reasons that aren’t just the War. Its reputation is about the practicality, diligence, friendliness, and whimsy embodied in everything from construction site warning signs and restaurant menus to subway turnstiles and, of course, toilets.

The cars. We walk out of Haneda Airport and immediately fall in love with and marry several trucks and sedans. They’re pink and blue. They’re tiny. They’re snub-nosed. We’re smitten.

The food. We eat onigiri from 7Eleven every morning and it’s filling and nutritious. We eat humongous courses of sushi, delivered one-by-one to our plates, for $12 and weep. Throw a shrimp cracker or a rice-derived Bugle in the diet once in a while. And soo much ramen, soba, and udon. Our stomachs don’t hurt. My skin is not oily. I’m harmonized among the macronutrients, a visitor among the wise and righteous.

Much ado is made about the contrast between Asian societies’ “collectivist” mindset and America and Europe’s “individualist” mindset. Collectivism being the idea that you value the shared goals of the groups you’re a part of—your family, your workplace, your country—more than some of your own expression and desires. And individualism being the idea that you’re a discrete unit of flesh and blood, that you don’t owe anything to anybody, and that your job is to make sure your own wants and needs are satisfied.

Highfalutin anthropologists go as far as to suggest that collectivism emerges where people rely on rice because rice farming requires collaboration, whereas wheat farming can be done by one person with some animals or machines. They argue that the different crops give us a sort of generational “play nice” or “play alone” disposition. Who knows if that’s true. But I can tell there’s a particular feeling to walking on the street in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto: less frenzied, more forgiving, even when you’re in the busiest throngs.

It feels like there’s less anger in Japan than in the United States. We are at each other’s throats on the street in our cities. Squeezing past or bumping into one another is a small but weighty violation. We’re competing to be first on the platform, first out of the plane, defending our place in line for an ice cream cone, afraid of being left behind and deprived, afraid of losing our spot.

This is what zillions of writers over the past two centuries observe (beginning with Tocqueville? earlier?) and sometimes call “the rat race.” It’s grody, it’s obvious.

Of courseee generosity and patience also abound in America. I’m partial to the Midwestern flavor of American kindness. We’re quick to cede a right or a privilege, to make amends, to check that we’re not stepping on someone else’s toes (literally and figuratively), all while sticking up for ourselves.

But Midwesterners, as Americans, are still defensive. Worried. Pissed off while we drive and pissed off online. Even when we think we’re not pissed off we are. It takes full attention to see the anger we carry around and to vent it someplace safe.

Why are we mad? In the broadest, dumbest terms: We don’t have enough money (wages are suppressed),1 nutrition (food is ultraprocessed and empty),2 healthcare (insurance is expensive and confusing), and fulfillment (jobs are hard to leave and entrepreneurship is moated)3 because of, in one inadequate word, oligarchy. And instead of being mad at the people who perpetuate oligarchy (and ourselves for providing its base fuel, coerced as we are), we get mad at each other. We don’t know what to do about it.

(Some people take the sublimated anger a quantum leap of sublimation further and blame specific ethnicities for this sorry state. Great!)

But in Japan. There’s this pervasive politeness. And it doesn’t seem like a shallow grit-your-teeth-and-bless-their-heart politeness. It’s not about warmth or deference. It feels more like a deeply ingrained sense of “being in it together.”

When we’re two taxis driving toward each other on a one-lane side street, it’s a problem for us to solve, not a slight to be punished. I was a passenger in one such fated cab in Tokyo. About two and a half seconds in to the same scenario in the U.S., opposing drivers’ family members would be cursed and someone might even have a new hole in their body.

During meals out with local acquaintances, I thought at first they spoke rudely to servers. But now I think it was more like: We’re equals, we’re doing quick business; you want to know my order and I’ll tell it to you. There’s no need for a careful tone or pity if basic camaraderie exists. The server isn’t sorry to be serving you and you’re not sorry to be served!

The same pattern comes out in pedestrian life. You might think national politeness means copious apologizing for sidewalk collisions and never-ending stalemates. (“No, you go!”) But really it just means most people walk deliberately, with some radiant mutual understanding. There’s very little negotiation. It just works.

Maybe most telling of all, there’s the infrastructure for blind people. I could hardly find a sidewalk or a public building that didn’t have yellow tenji groove guides for people who use white canes. And this is built on top of cities that were founded 500 or more years ago. In the parks, we came across multiple groups of blind joggers with their wrists tethered to sighted guides. And Japan leads the world in disaster preparedness, a title borne out of necessity but a reflective one nonetheless. The ultimate collectivist flex: paying taxes to mitigate future catastrophes.

If I can really go out on a limb here, I’d say all of these anecdotes give the sense that, for city dwellers in Japan, there’s more awareness of the principles and circumstances that define a conflict, and focus on resolution, than on the fact of the conflict itself. When faced with something shitty, my imaginary Japanese Homer Simpson thinks, Did the others involved do something unreasonable? Were they reckless or greedy? Or is it merely the way the cookie crumbled? Either way, how can I just fix it and move on?

When there’s more of an “in it together” feeling, we’re less primed to think that a stranger is depriving or slighting us, that we have to defend ourselves. Maybe in turn the stranger is actually less primed to deprive or slight us. That sounds like a virtuous cycle to me, even if it’s a grossly oversimplified one.

Meanwhile, I remind myself why Americans are angry in the first place. They say it’s easy to be nice when you’re rich. It’s also easy to be patient when your patience isn’t tried all the time. All the unmet needs I mentioned earlier have a way of eroding one’s patience. And patience-deflated people have a tendency to go out and do things that sap patience out of other people. (I’m not excusing us, I’m just recognizing us.)

There. A vicious cycle. More selfishness, causing more fatigue, causing more selfishness. Oy vey.

In contrast to Japan’s: abhorrence of selfishness making slights less common, making unselfish behavior easier to carry out. Even while the value of the yen is low and work is hard.

What a relief to have a break from our cycle.

But there’s a problem. A new friend from Tokyo told me that collectivism can be tiring. You have to curtail a bit of yourself to meet this expectation of service and maturity all the time. It’s hard, even if you buy into the belief that we really are better off helping each other.

Japan may be less angry than the United States but maybe at a cost of a low-grade dissatisfaction or longing for more freedom and looseness. Like I relish the chill of their cities, some Japanese people might envy the American God-given option to be a dick, to revel in ourselves, to take up space, to be loud and to mold our surroundings. At least to honk your car horn. (Maybe the simplest comparison of New York and Tokyo is that one has so many dedicated, passionate horn honkers that we have to make unenforceable laws about them. The other has a shopping district so quiet you can just… talk in it.)

What we want, probably, is a balance between Tokyoite restraint and New Yorker freedom fire.

Fun freely flowing, slightly loose steam valves, with a steadfast, wholly understood commitment to collaboration and reason. Assuming good things of each other. Building the delicate trust to share food instead of eating as much as we can before our siblings take it all.

Willingness to sacrifice for the group coupled with the recognition that, as a part of the community and the universe ourselves, individuals need and deserve pleasure and fulfillment, too. Take care of yourself, put on your oxygen mask, etcetera. You’re your keeper. You have a duty to the neighborhood and yourself. Some kind of Middle Way.

On this tour, I think we put this balance in action. At least we strove for it.

We noticed and respected norms. We tried to integrate. But, oh, the way we “took up space” in Japan. As a non-traditional family band unit of two parents (Sima and Dorian), a baby (Zulal), and two loving auntie/uncles (Macie and me), we enlivened subway cars with baby laughter and stopped sidewalk traffic with Google Maps consultations. (Though in cases like this I question whether we were really “taking up” anything or just… being part of it. It wasn’t a symposium or a board meeting where the meek and marginal got excluded, after all.)

We tried, we were ourselves. I’m not proud of our friction with the culture, but I’m proud of our joy. And I don’t think any Japanese onlooker begrudged us for it. I saw them say:

Hello!

Chk chk chk!

Cute!!

And take pictures of an American marshmallow.

American Bar Association: “America’s Vast Pay Inequality Is a Story of Unequal Power.”

So much to enjoy and reflect upon here! But I’ll keep it short this time and just say I always come away feeling better for reading what you’ve composed.

I really loved this, Spencer. Sensitive,

observant, insightful and very entertaining.